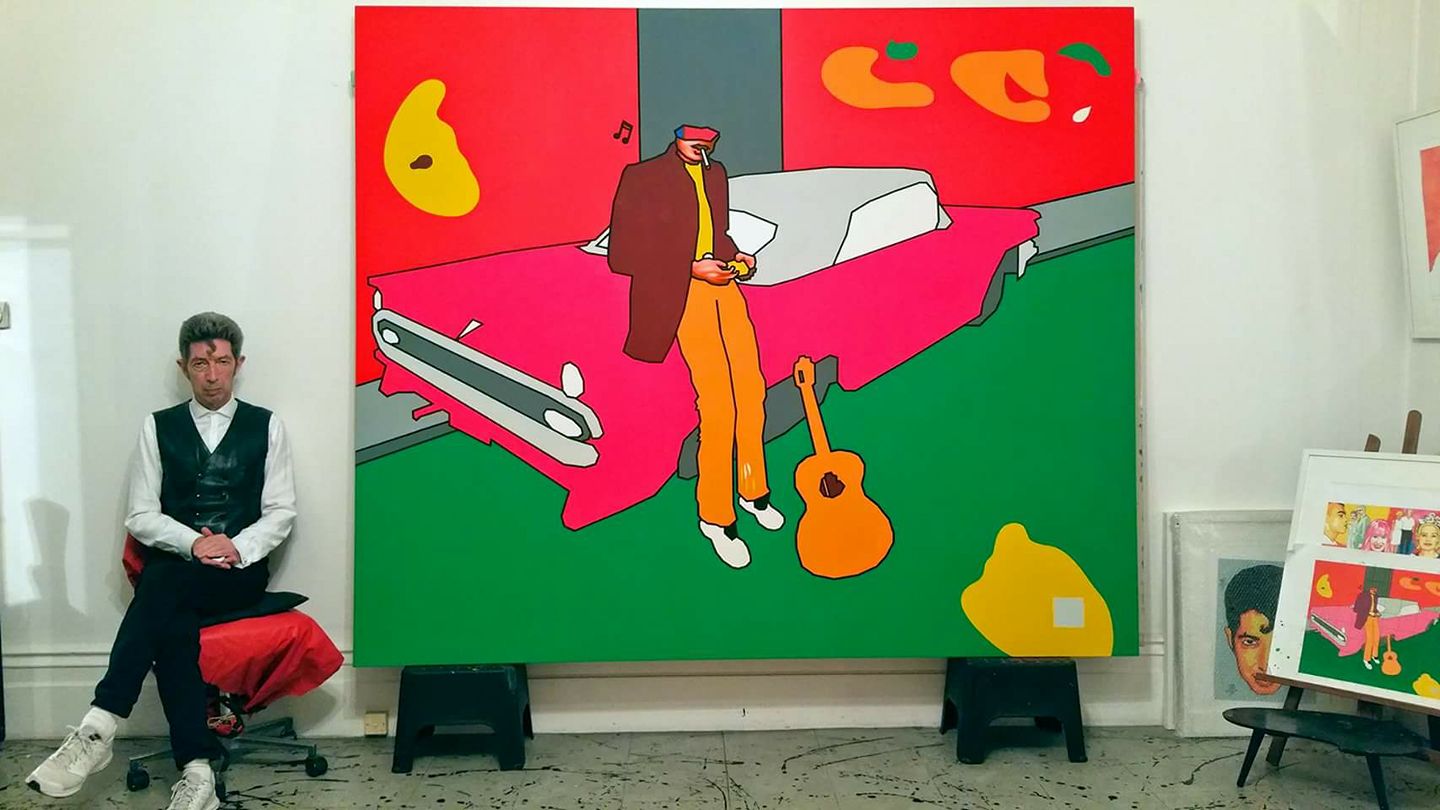

As one of Duggie Fields’ paintings portraying Syd Barrett makes its public debut at The V&A this month, part of the Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains exhibition, BLOW! catches up with the artist to talk about his old flatmate, and an artistic journey spanning almost five decades.

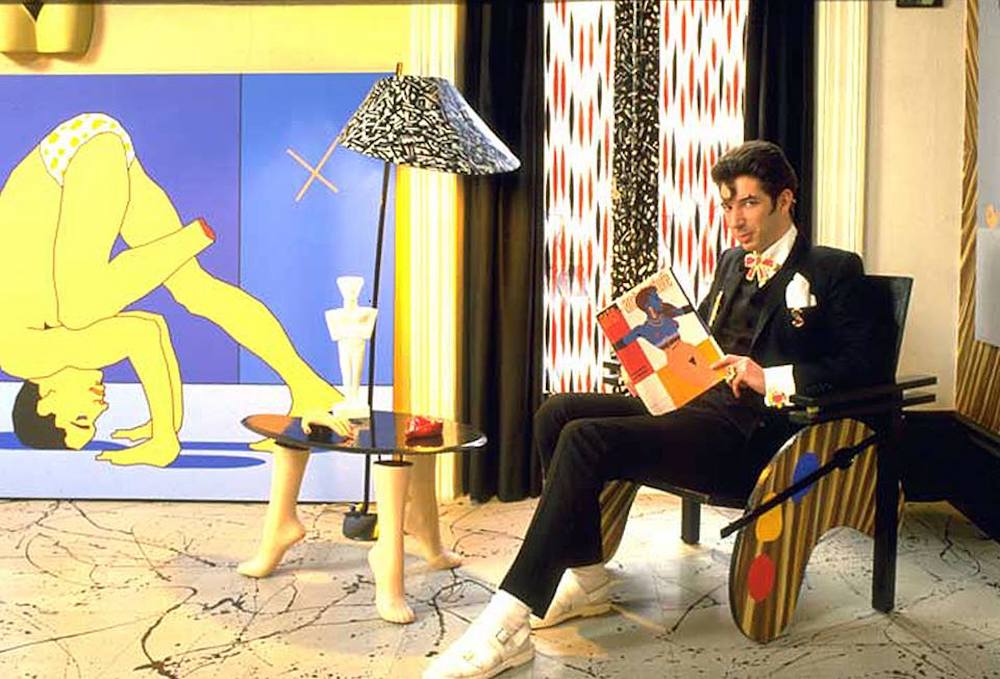

Having trained at the Chelsea School of Art during the ‘60s, Duggie Fields’ work includes video, sound, digital imagery and his hand-painted canvases for which he is best known. With a life as colourful and eclectic as his creative output, he has walked the runway for Comme des Garçons, featured in a Sheisido campaign and was the subject of a Japanese obsession during the 1980s.

First of all what inspired you to paint the picture of Syd?

Well it wasn’t painted specifically for this exhibition. The painting took almost a year to do and I only connected by chance with the curators the day before they were finalising the show selection. I’ve tried to paint him several times over the years and I’ve been asked to paint him before by various people and for exhibitions, but it never worked out. I still live in the same flat in Earls Court that I shared with Syd, so I do get echoes of him and I also encounter his fans that sometimes hang around outside. So he had, and continues to have, a very bizarre role in my life. For this painting, I just suddenly knew how to do it; the timing was completely fortuitous.

Duggie Fields with his Syd Barrett painting

How did you and Syd come to meet?

While at art school I ended up sharing a flat with Roger Waters and others I’d met at architecture school. The flat was at 101 Cromwell Road. It had seven rooms with nine or so people usually living there at any time. Roger had known Syd since childhood and he subsequently moved in. After a while the building was earmarked for demolition so I eventually found a flat in Earls Court and Syd moved in with me. We lived there together for about two and a half years. This was from the winter of 1968.

The Times recently singled out the painting as an exhibition highlight. How do you feel about criticism?

Firstly there is no correct response. There’s only the individual and what they see and if I like them I don’t mind what they think or how they interpret what they see. It’s nice when people respond positively but I’m always lead by my own response. You need to have that strength of feeling to be an artist.

Did Pink Floyd’s success come as a surprise?

In 1966 they were rehearsing at home and by 1968 the band was on their second tour of the States without Syd. It all happened very quickly for them. They were interesting, but their success wasn’t necessarily expected. I remember thinking I wish this band had a better sense of rhythm so I could dance to them while they rehearsed at home at 101. Having said that, I had already seen huge success blow up very quickly. In the mid ‘60s I used to go to a small club with an unsigned house band that did covers. They were the Rolling Stones.

I read that you were influenced early on by Jackson Pollock. Is that true?

I spent my childhood living in the country. We had a small black and white television and I remember when I was about thirteen catching a short piece on Jackson Pollock. The presenter was taking the piss a bit, modern art was still frowned upon, but something about his work and approach made an impression on me. Afterwards I found some paint and paper, went outside onto our small terrace and started experimenting with the paint, letting the wind do its thing.

You’ve described your work as ‘post-Pop figuration’. Can you elaborate?

I hate being boxed in when images communicate in a completely differently way to words. I would say ‘post-pop’, as when I was a student ‘pop’ was already established. Figuration speaks for itself but I see my figures as abstract elements. For me, parts of the figure can symbolise the whole, and putting in certain parts but not others can invoke a particular emotional response. There’s also a geometric element as I still use a base grid structure and I compose with straight lines. Ultimately I’m looking to make images that connect intellectually and emotionally, I’m not worried about anatomical correctness. For me it’s an intuitive work process.

You seem to have an equal passion for pixels and paint.

I first started using digital video in ‘97, having only got a Mac in ‘95. I thought I was just going to do collage and archive my past but I soon discovered you could do movement and sound. After a few starter lessons I pretty much taught myself to do music, production and animation. Practically, painting is mentally and physically challenging, I do a lot work on the floor sitting half lotus. In terms of a hierarchy, whatever I make is whatever I make and it’s of equal significance to me. If there comes a point where I can’t paint, I’ll probably spend more time sitting at the computer.

You were the subject of a Japanese obsession during the 1980s and starred in a Shiseido campaign. How did that happen?

One day they called me directly out of the blue. I’d done a few interviews for big Japanese magazines and had been approached by others offering books, TV appearances and exhibitions, but nothing ever actually happened. This particular day, I was sitting at home watching a soap opera thinking about how I’d pay the rent that month. The phone rang and it was someone from Shiseido, saying they wanted me to be in a campaign for them, and that they were coming to London in 10 days. I met them, agreed the particulars and headed to Japan. I knew the name but didn’t really know how big they were. The whole experience was a bit like ‘Lost in Translation’ but without Scarlett Johansson. Despite having an interpreter most of the time I didn’t really know what anyone was saying. At the time Shiseido allowed me to carry on working.

At the airport on the way back after Comme des Garçons more than twenty years later, I was told by the passport checker that I was Kawaii (cute). My passport got passed around the immigration desk with her colleagues agreeing. I guess something about me had a cultural appeal. I was upgraded as a result.

You have a definite personal style. What’s the relationship between being an artist and expressing yourself personally through your image?

I’m the kind of person I am and I operate visually. The geometric frame one works in does have a special potential that other things can’t have but it’s not isolated. I do things outside the canvas to better understand the canvas. Some days I’m more colourful than others. There’s no consistency, for example I had two big events this week, for one I wore black.

Today’s world seems quite bland compared to the ‘60s. Do you see a point where there will be nothing alternative left?

Well, what seems excessive becomes normalised and that’s a fascinating process. All sorts of things, rubber-wear for instance, was fetish-only and seemingly bizarre. Now we see rubber in Vogue. That said, things can regress, certainly censorship and brutality can. The ‘60s was about love and peace, a reaction against the war in Vietnam, and that counter-culture was a large one. Look at where we are at today with Trump, Brexit and the rolling back of LGBT rights in places like Russia.

You’re a fervent ‘Instagrammer’. What do you make of social media?

I remember when communication was a phone on a table in a hallway. I also remember the challenge of trying to find a non-vandalised phone box. In many ways I love the fact that I’m connected with all these people that I haven’t seen for years. I also love the random discovery of people I don’t know, and like the fact that a mainstream journalist didn’t have to present it to me. I also like the exponential capacity to link and link and link. On a practical level it’s also somewhere to store imagery. I used to put photos in albums and the glue would deteriorate them. What I share isn’t going to decay unless there’s a cyber attack.

What’s next?

I’m in talks with a French record company about doing an album. That was never a plan but has come about indirectly through a chance past echo connection. A famous French musician fan of Syd’s discovering himself close by made a ‘pilgrimage’ to the flat, knowing my art but discovering my music work in the process. We’ve since become friends and he introduced me to the label. There are exhibition things happening too, but I really just look forward to continuing. I’ve usually got something creative––painting or digital––underway and I want to carry on finishing, and then starting again.

Pink Floyd: Their Mortal Remains runs at The V&A until the 1st of October.

Follow BLOW! Magazine on Instagram here.